Two #tbt interviews with photographer Lester Blum and artistic director Vladimir Rios originally published in A&U Magazine

In Memoriam…

Photographer Lester Blum and creator and artistic director of “I Still Remember” Vladimir Rios talk about their new show opening on World AIDS Day

by Alina Oswald

When all is said and done, memories are often all that we’re left with. A granny’s voice, a mother’s face, a best friend’s smile remain forever imprinted in our minds. and hearts, there for us to tap into whenever we still need that voice, face, or smile. And as long as we remember them, they are still with us, part of our lives.

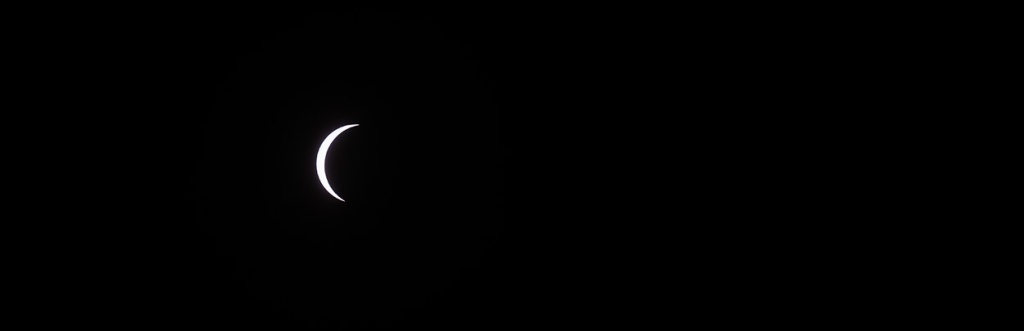

The AIDS pandemic has decimated communities, replacing hope with despair, light with blackness, leaving behind a deep and dark void, while taking away loved ones, too often, too soon. But that doesn’t mean that those lost to the pandemic are lost from our lives. We still remember them, and keep their memory alive.

“[We should still remember] because that’s the only way that we’re going to keep people [who passed away] alive,” actor and artistic director Vladimir Rios says, as I sit next to him and New York City photographer Lester Blum, sipping on tea, in a cozy coffee shop in Chelsea. “I lost my grandmother,” Rios continues. “She was an absolutely great human being, and, to me, [losing] her was a big deal. I was quite young when she died….I noticed that by keeping her memory alive, she never really died. She’s always with me.”

The idea behind their most recent photo collaboration, “I Still Remember,” is multi-fold—the desire of keeping the memory of loved ones alive, the desire of educating younger generations about the history of HIV, and, well, the result of pure chance.

Vladimir Rios and Lester Blum met a decade or so ago on the set of a photo shoot—Rios was the model, and Blum, the photographer. They became very good friends, and then started collaborating on other photography projects. And they’ve been doing that ever since.

The first project, “Despair,” is a body of work capturing an individual’s journey from the darkness of despair and back into the light, because (as mentioned on Lester Blum’s website) “[u]ntil our own darkness is understood, we can not even begin to try to understand the light.” Mentioning “Despair,” the photographer explains that it was the first collaboration, which was entirely created by Rios as the artistic director and model. The lead image of the series has been exhibited in four photography shows, and won several photography awards.

Another more recent show, “Warrior of Hope,” offers a visual representation of a fictional, but much-needed hero personifying “the concept of ‘hope’ for a better future, in a constant battle against inequality, injustice, and disease.” Blum explains, “‘Warrior of Hope’ was already scheduled for exhibit at the Pride Center of Staten Island, this fall. In a discussion with the curator, he indicated that they were looking for a powerful exhibit, which could be shown in Staten Island in honor of World AIDS Day. The following week, we presented the concept for ‘I Still Remember,’ which they immediately fell in love with, and believed it was the perfect project to honor World AIDS Day.”

Blum points out that both “Warrior of Hope” and “I Still Remember” are visual narratives. One is based on fantasy, while the other, on reality. In that sense, “I Still Remember” serves as a remembrance, but also as an educational tool for the younger generations. “People who are ill always need hope, so those presented in ‘I Still Remember’ need the hope as personified by the Warrior,” Blum comments, drawing parallels between the two shows.

Conceptualized by Rios and photographed by Blum, “I Still Remember” offers a striking, riveting, a brutally honest and powerful visual narrative of a universal story of love and loss at the height of the AIDS pandemic. It tells the story of two men who meet, and fall in love. One of them, played by Rios, becomes sick. The other one, the main character of the story played by adult entertainer Scott Reynolds, lives to tell the story as he (still) remembers it. “‘I Still Remember’ captures vignettes of life—how they met, while they were together, and after one dies of complications from HIV/AIDS,” Blum says.

The photography for “I Still Remember” actually started in the fall of last year, with another project called “Encounters.” It just happened that some of the images from “Encounters,” showing how the two characters met, ended up part of “I Still Remember.”

The show touches on every facet of life as it was, in turn, touched, directly or not, by HIV during the eighties and early nineties. Every image included in the show visually and vividly captures a facet of that reality. Each character brings his or her own uniqueness and experiences to the story, in turn, enhancing the reality of the story.

Rios, himself, brings his own experience to the show. The Puerto Rico native worked in New York City as a social worker for many years, helping, among others, people living with HIV. About ten years ago Rios moved on to pursue other interests in life, but his experience as a social worker, especially related to HIV and AIDS, has influenced his very own view and interpretation of “I Still Remember.”

“We didn’t want to hold back anything,” Rios explains, talking about the importance of expressing the reality of those years, as shocking as it might be. “[We didn’t want to] soften the visual imagery that we would present to the viewer. We wanted to show the reality of that era, with real subject matter.”

He starts flipping through several sample images that Blum had brought along. Both the photographer and artistic director comment on each of the images, finishing each other’s thoughts, making sure that they cover all the details, their voices filled with passion…and also pride. There is the drug scene photographed in the Meatpacking District featuring a few real drag queens, members of the Imperial Court of New York. There is also the sex club segment “made possible by the generosity and project support of Hunteur Vreeland of HandsomeNYC.com,” Blum adds.

There’s a scene of an actual doctor actually drawing blood from Rios’ arm. Years ago, Blum was looking for a new family doctor. Somebody suggested Dr. Arthur Englard, who’s also an allergist. As HIV started to spread, the doctor also specialized in HIV. He agreed to be photographed for the “I Still Remember” show.

A poignant image portrays Rios’ character on the beach, reflecting on his diagnosis. Some of the most striking images come at the end of “I Still Remember.” They capture the memorial of Rios’ character, showing the surviving partner surrounded by friends, holding his lover’s ashes. The box he holds in his hands contains actual ashes, those of one of Blum’s friends, Louis F. Petronio, who died of AIDS-related causes in the early nineties.

“Everything that we have done is as real as it can be,” Rios reiterates. “We [also shot] a series in which the friends [of the main character] are disappearing, one by one. This is symbolic, because not only he lost his boyfriend, but he did lose his friends, [too]. So, there’s a very powerful sequence [of images] that we captured on the beach, with five friends walking on the beach, and then there’re four, and then three, two, and then he’s alone. Because [in those days, people kept dying] of AIDS, and kept disappearing.”

There are several images showing individuals laughing and having a good time. That’s because Rios and Blum wanted to project not only the sad moments, but also the lighter ones. “They did have fun,” Rios says. “They did have friends. They did enjoy life. That’s why the memories are so important, because no matter the cause of their death, they were wonderful people. They were great people to be remembered. Whether you’re in approval of their lifestyle or [of] who they were or what they did, it doesn’t change the fact that they were in our lives. They were people who were loved. So why wouldn’t we remember someone who was a good human being, whether they did drugs or were sick or had a wild sexual life. Why not remember these people and [cherish] the good memories that they gave [us].”

To start working on “I Still Remember,” Blum and Rios put out several postings, looking for individuals who’d want to participate and be photographed for the show. Photo shoots took place in Manhattan, Staten Island, and also on Fire Island. A final photo shoot capturing the bedroom scene shows Rios’ character being sick, in bed, succumbing to the disease. In addition, the show also captures segments focusing on controversial religious beliefs as well as family rejection related to HIV and AIDS.

“I Still Remember” is not only an eye-opening, powerful work of art, but also an educational tool. “The [Pride Center of Staten Island] saw it as an educational tool for the new generation,” Rios explains. “It was the best compliment that they gave us.”

Discussing the educational aspect of “I Still Remember,” Blum adds that the show “is a reminder for the existing generations that either lived through [the height of the epidemic] or came right after, [as well as] an educational tool for [today’s young generation]. Right now there’s so much hype on things like PrEP,” he says. “People don’t know [enough] about it, yet they’re taking it.” He and Rios point out the socio-economical divide that PrEP might add to the already complicated, yet still unsolved equation of HIV and AIDS. That’s because, while many health insurance plans cover PrEP, others don’t. And then, being on PrEP or not could become an issue of class and social status, of who can afford it and who cannot.

Blum adds that today’s youth should know what those that came before them went through—how the epidemic affected not only their health, but also their entire lives, on so many levels. “I know people who’ve had the virus for thirty years now,” he says. “Their lives were affected in many, many ways. [Even right now] the disease is pretty much controlled for a lot of people, and yet, it’s much more than just a disease. And I think that the younger generation that didn’t live through this…they need to know this.”

“I Still Remember” opens on December 1, World AIDS Day, at the Pride Center of Staten Island, and will run, tentatively, through mid-January. There will be thirty to thirty-five images in the show. There are also possible plans for the show to travel nationally and internationally.

“I think it’s important for people to remember their loved ones, to keep them alive in [their] hearts and minds. I want people to walk away [from the show] knowing that. It’s the most important thing to me, other than [“I Still Remember”] being an educational piece of [artwork],” Rios concludes.

“I would like a two-fold experience for people,” Blum adds. “One is to not only remember the individual, but also to remember what happened to our society as a whole during this timeframe. And somehow [that] memory to make a difference today, to encourage more research, more safety measures, because just like I said with the Warrior [in “Warrior of Hope”], the battle is not over. So much more still needs to be done, and education is a big facet. I want people to understand that.”

Learn more about “I Still Remember,” “Warrior of Hope,” and Lester Blum’s photography work at www.lesterblumphotography.com.

Veils & Visibility

In Their New Photography Show, Lester Blum and Vladimir Rios Help Shed Light on Individuals Living with HIV & Others

by Alina Oswald

Only days after the shooting at the Pulse club in Orlando, I find myself at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Center in Manhattan to meet with photographer Lester Blum and talk about his new show, “Invisible.” I arrive at the Center a few minutes early. Looking around, I notice a police van parked right in front of the Center, flanked by two police officers, who were dressed in what looked like full body armor. I point that out to Lester Blum, as he arrives a moment later, and we walk by the officers and greet them. They greet us back, and even smile at us. We conclude that they’re there for protection, to keep an eye on things, as they say. From the look on Blum’s face, it seems to me that he has much more to say about Orlando, and we hurry inside to talk about that, as seen through the prism of his new show, and much more.

While many of us are familiar with the work of Lester Blum and Vladimir Rios through shows like “Warrior of Hope” and “I Still Remember” [A&U, November 2015], with “Invisible” we have the chance to rediscover these amazing artists, and to be introduced to a new facet of their work. “Invisible” is a multilayered documentary that takes on the topic of invisibility in our society. (Opening night is August 13, at the Pride Center in Staten Island, which is also planning several educational events around the event.)

When I spoke with Vladimir Rios later, I learned that the idea for the show started with a simple conversation Rios had had with a man in a wheelchair on the beach at Fire Island. At the time Blum and Rios were still working on the “I Still Remember” photography narrative. The man, Bruce Paul, thanked them for taking a moment to chat with him, commenting that usually people didn’t acknowledge him, let alone talk to him, and thus making him feel invisible. And so, Rios decided to make his story visible. The man in the wheelchair ended up being the first (out of a group of up to twenty people) to be interviewed for the new project.

“He planted the seed in my head about doing a project about people who are or feel invisible in our society,” Rios emphasizes later, when I catch up with him. “Of course, I took the opportunity to learn more about him,” he adds, “and immediately felt that I wanted to present this concept [of invisibility] in an artistic manner,” to offer not only a way to learn about these individuals, but also to learn how to make a difference in their lives.

“Having been a social worker for many years,” Rios adds, “I was aware of individuals who suffered from [feeling invisible]. The encounter with Bruce brought the subject, which we tend to ignore, back to the surface. I was very curious to learn how someone who felt invisible actually felt.

“The initial thought about this project was strictly to present people with obvious physical challenges and disabilities. When Lester [Blum] and I actually began [working on] the project, we quickly learned about the variety of causes that were not necessarily [related to] physical disabilities.”

While working on the project, Blum and Rios have encountered many other facets of invisibility, either because of an HIV status or being considered “different” in society—being born with HIV; bullied as a child or adult because of being gay, small in size, not athletic or overweight to name only a few; being sexually abused; aging; living with mental illness; and many others. And they noticed that all stories had a common thread—they were all related to feeling damaged or not belonging, or related to anguish, depression, and even suicidal tendencies.

“The project is different from others,” Blum tells me. “[While] the others were primarily fictionalized stories, based on actual things—‘I Still Remember’ was a combination of so many people’s lives from that era [the beginning of the AIDS pandemic]—‘Invisible’ is a multidimensional documentary combining still photography [portraits], written testimonials, and documentary style video. It is about actual people’s lives, their feelings and emotions.” Blum was in charge of the photography and videography, and Rios, the creator of “Invisible,” interviewed those who wanted to share their stories for the show.

Invisibility comes in all shapes and forms. Some are more subtle than others. Hence, individuals interviewed for the show cross all walks of life. While some find hope again and become visible in society, others choose to become invisible as a defense mechanism, hence they project to the world only a facet of themselves accepted by society.

“The other side to that is Orlando,” Blum comments, explaining that those killed in Orlando might become invisible because they’re not alive anymore. “We have to give them a voice,” he adds, emphasizing the importance of keeping them visible, remembering them. “Since the tragedy which occurred in Orlando,” he adds, “we [Blum and Rios] feel even stronger about the message of the project and the educational aspect that the project entails. Those who perished no longer have a voice. ‘Invisible’ [marched] in NYC’s Gay Pride Parade to emphasize that we, as a community, are no longer invisible.”

Rios also adds, “In today’s world, being gay [still makes] many of us invisible in society. Many of us choose to stay invisible to be safe. For many, the attack in Orlando re-emphasized the necessity of staying invisible, [while giving others the courage to become visible]. While not affected directly by the recent Orlando massacre, everyone in the LGBT community and throughout the world was greatly affected by the tragic event. What’s most relevant is that the entire world basically unified in showing support, compassion and love for the victims, families, and friends. We cannot afford to let anyone feel invisible. We are all part of the same world. In memory of the Orlando massacre victims, I refuse to ever be invisible.”

What both Blum and Rios discovered while working on “Invisible” is that invisibility is multi-layered. At some point in their lives, many individuals have experienced some deep-seated feelings of being invisible. The artists also found out that everybody deals with the issue of invisibility in different ways.

Although each story is unique and relevant, some stand out more than others. So is the story of Raymond Scott VanAnden, a man living with HIV who has been abused in multiple ways during the time of his last relationship. When interviewed, Scott says, “Sometimes the feeling of being invisible keeps us safe from life’s issues of abuse or neglect or disease…it can be the comfort from life’s issues.” Rios says, “What makes his story remarkable, is that he turned his life around and now works as a counselor at an HIV center, helping others.”

There is also the story of Andi Poland, who lost two sons to suicide within a short two-year time period. “After her loss,” Rios says, “this amazing woman has chosen not only to help herself, but also [help] others by learning about mental illness and suicide. She hopes that society becomes educated about the subject, so that no one else will have to suffer [losing] a loved one to suicide.”

But not all “Invisible” stories are sad stories; quite the contrary. Some offer hope and the possibility of becoming visible again. Some highlight that very dim, but present silver lining or the light at the end of the dark tunnel of invisibility, while others help us reach inside ourselves giving us a chance to touch base with our own humanity.

For example, artist and activist Robert Ordonez has become a staple in the New York City scene and beyond for his work behind and in front of the camera. “Sometimes I want to be very honest about who I am, and that scares people,” he says. “My attitude in life is [to] go for your dreams, no matter how many people or what obstacles try to slow you down.”

John Chamness comments that being born with HIV, as he was, “is like being born with green eyes, completely out of the child’s control. But it’s a birth into stigma, in the strongest sense. I have spent my life not being able to let people see or know all of me, just part of me.”

There are also stories of compassion and unconditional love, such as the story of Caroline Loevner and her dog, Beau. See, Beau is a formerly abused, beautiful (indeed) Alaskan husky, who now is a therapy dog. Beau and Caroline work together, and they make a great team, helping people, “bringing hope, love, and compassion to those in need,” Rios explains. “What they do is something to be admired and perhaps, emulated.”

Beau is a busy dog. His “steady gigs” include weekly stopping by Rivington House (founded by James Capalino in 1995, at the height of the AIDS crisis, to help a community in need; nowadays the facility is only partially full); Beau also stops by Terence Cardinal Cooke Health Care Center, Beth Abraham nursing home, in the Bronx, and also the Ronald McDonald House, offering comfort to children living with cancer and their families. “Maybe we can learn something from [dogs like Beau] from what we consider ‘lower species,’” Blum says, showing me a few pictures of Beau, by himself, giving Rios some love or posing for a portrait with Caroline.

Art is a powerful tool to tell in particular this kind of stories. “In ‘Invisible,’ the visual and verbal go hand in hand to convey the full story,” Blum comments.

HIV is present in each and every one of the visual narratives he created together with Rios. HIV is present not as an isolated issue, but rather as part of a bigger story. And I have to ask why.

“That’s a complex question,” Blum answers, “because the answer is multifaceted. I think that the main answer is the fact that HIV is a part of our world today, and it’s not going away anytime soon. People are affected. New people are getting sick, whether they’re from the LGBT community or the general population.” He adds, “With treatment, people are living longer, but I think that it’s important that people keep being made aware of HIV, AIDS, and not falling into the fantasy that taking PrEP is going to be the cure-all. And even in the medical community, they’re talking about the same thing. [PrEP] is not the miracle pill.” He believes that this ongoing HIV and AIDS awareness is important as a reminder for older people, for those who were around during the eighties and nineties, but in particular for younger people, so that they can “think about [HIV] and think about what they’re doing.”

The “Invisible” feature image, Lifting the Veil, defines the message, the mission of the show itself. “That’s what we want society to do, to lift this veil, so that the various and diverse issues faced by people are no longer invisible, giving others the opportunity of [more] understanding. We must become more accepting of each other,” Blum says. In speaking with the participants, Blum and Rios realized that by giving those individuals the opportunity of talking about their issues, they also helped these individuals suddenly become visible, at least to a degree.

To which, Rios adds, “The goal of ‘Invisible’ is to create a forum where people can have a voice where they can be heard and not hurt. [The show] is an educational piece that will hopefully help people to respect others, accept them for who they are, and welcome them as part of our society.”

Find out more about Lester Blum’s photography work by visiting him online at http://lesterblumphotography.com/.

Leave a comment