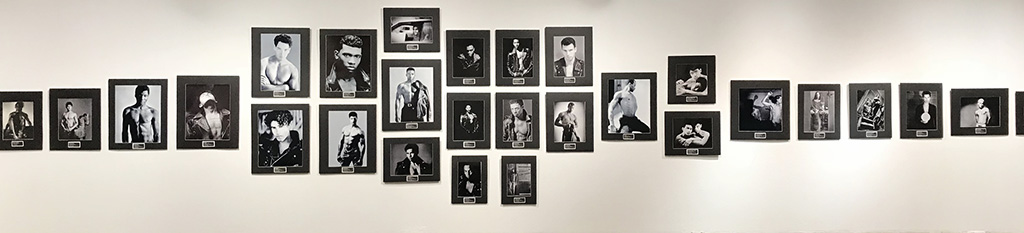

A look back at the Blind Vision series of black-and-white self-portraits by award-winning photographer Kurt Weston

I’ve interviewed award-winning, legally blind photographer, Kurt Weston, several times–for A&U–Arts & Understanding Magazine, Out IN Jersey Magazine, and Journeys Through Darkness: A Biography that traces the photographer’s journeys through the darkness of AIDS and related blindness.

Here are a few excerpts from all that writing, in which Weston talks about the making of his Blind Vision series of black-and-white self-portraits:

Photographer Kurt Weston received an AIDS diagnosis in 1991. At the time, such a diagnosis was considered an immediate death sentence. Still, Weston survived. Several years later, the first life-saving medications became available, saving his life. Yet, they were too late to save his eyesight. While trying to restore his health, the photographer was also becoming legally blind and was diagnosed with CMV retinitis [AIDS-related retinitis] in 1994.

This is his reaction to that diagnosis and what followed after learning that he was probably not going to photograph again:

““I was devastated because here I had spent my life working as a photographer and visual artist, and I was no longer capable of doing this…or so I thought because I couldn’t see anything in focus. I don’t see anybody’s face. I see…as if I look at the palm of your hand.That’s what I see of aperson’ss face. So, Ididn’tt think I could ever photograph again.”““I was devastated because here I had spent my life working as a photographer and visual artist, and I was no longer capable of doing this…or so I thought because I couldn’t see anything in focus. I don’t see anybody’s face. I see…as if I look at the palm of your hand. That’s what I see of a person’s face. So, I didn’t think I could ever photograph again.”

Fortunately, it turned out he could. His first challenge was to photograph the 1999 calendar for the Asian/Pacific Crossroads.

Many challenges later, and after attending low vision technology studies at the California Braille Institute and experimenting with special equipment, Weston realized that he could, indeed, photograph. With the help of organizations like the Foundation for Junior Blinds (then known as Junior Blind of America) and the California Department of Rehabilitation, he purchased the gear—handheld telescope, special magnification glasses, and magnification and reading software programs like ZoomText—necessary for him to continue his work.

““It was scary”” he says.“”A lot of times, I would take a leap of faith and do a lot of experimentation,” he recalls this learning process.““It was scary,” he says. “A lot of times, I would take a leap of faith and do a lot of experimentation,” he recalls this learning process.

Yet, Kurt Weston firmly believes that a person can work through a situation, no matter how extraordinarily challenging and helpless it may seem, and then use the experience to help others who find themselves in similar circumstances. This philosophy has helped him work off the dilemmas in his own life while giving his life a more profound sense of meaning.

His early work in the AIDS community includes the founding of SWAN (Surviving With AIDS Network), a grass-roots organization, and the Orange County Therapeutic Nutrients Program. Both assisted people living with HIV and AIDS.

From his perspective, Weston considers art a vehicle through which we can experience the nature of humanity. In today’s society consumed by superficial realities, his art connects with the viewer on a more profound, spiritual level.

”KurtWeston’ss Blind Vision series of self-portraits shows people the physical and emotional impact that visual loss can have on an individual. Among the images included in this series, Losing the Light was the feature image at the VSA (Very Special Arts) show that opened in 2006, in Washington, DC, at the Kennedy Center for Performing Arts; also Journey Through Darkness inspired the title of his biography, which, then, led to Kurt Weston winning the CNN iReport Award for Personal Story, in 2012. To represent his visual disturbance—which he described as““pieces of cotton stuck in my eye, floating every time I move my ey””—he sprayed a glass with foaming glass cleaner and took a self-portrait behind it.““You see my hand pushing away the foam, which is what I would love to do”” he explains,““I would like to be able to wipe away all that cotton that keeps floating in front of my eye and get a clear view of what I want to see out in the world.”“Kurt Weston’s Blind Vision series of self-portraits shows people the physical and emotional impact that visual loss can have on an individual. Among the images included in this series, Losing the Light was the feature image at the VSA (Very Special Arts) show that opened in 2006, in Washington, DC, at the Kennedy Center for Performing Arts; also Journey Through Darkness inspired the title of his biography, which, then, led to Kurt Weston winning the CNN iReport Award for Personal Story, in 2012. To represent his visual disturbance—which he described as “pieces of cotton stuck in my eye, floating every time I move my eye”—he sprayed a glass with foaming glass cleaner and took a self-portrait behind it. “You see my hand pushing away the foam, which is what I would love to do,” he explains, “I would like to be able to wipe away all that cotton that keeps floating in front of my eye and get a clear view of what I want to see out in the world.”

”Weston believes that black-and-white offers his art a concentration of expression. And he likes that intensity, in particular in his portraits. He uses regular film and prints his images on silver gelatin paper so that they can last forever. He wants future generations to be able to look at this work and say,““This was happening at this time in history and this is the impact it left on people whose lives it touched, this pandemic.”“Weston believes that black-and-white offers his art a concentration of expression. And he likes that intensity, in particular in his portraits. He uses regular film and prints his images on silver gelatin paper so that they can last forever. He wants future generations to be able to look at this work and say, “This was happening at this time in history and this is the impact it left on people whose lives it touched, this pandemic.”

[…]

He believes that […] a cure will come. Until then, he reminds, there is so much work to be done.

Find out more about Kurt Weston’s photography work by visiting him online or stopping by the Orange County Center for Contemporary Arts.

As always, thanks for stopping by!

PS: Read the latest article (not mine) about award-winning photographer Kurt Weston in Shout Out LA magazine.

Leave a reply to Alina Oswald Cancel reply